Kyoto, the city of a thousand years. Its name is synonymous with the charm of old Japan, serene temples and shrines, and an appeal that continues to attract tourists from all over the world. However, beneath this glamorous image, a serious “silent crisis” is underway. “Kyoto City is a difficult place to raise children,” and “It’s not a place for citizens to live”—such harsh criticisms are now ringing at an undeniable volume.

This sentiment is particularly urgent among young people and families with children. In the city center, places that were once homes and local shops are being transformed one after another, with hotels and tourist facilities proliferating. The resulting soaring land prices and rents have become unattainable for the younger generation.

To substantiate these anecdotal claims, this article analyzes five graphs based on public data from fiscal years 2014 to 2024, focusing on the number of elementary school students in the city. Numbers, at times, eloquently speak the truth. Through this data, we will shed light on the often-overlooked reality of the educational environment and the challenges facing families with children in Kyoto City.

Source: Kyoto City School Basic Survey

- 1. A Shocking Reality: A Decline of 10,000 Students in 10 Years, Equivalent to One Elementary School Vanishing Annually

- 2. The Hollowing Out of the Center, The Vanishing of Communities: Disparity Revealed by Ward-Specific Data

- 3. The Light and Shadow of the Educational Field: The Benefits of Small Classes and the Crisis of School Survival

- 4. A New Trend: Hope and Challenges Brought by Diversifying Nationalities

- Conclusion: Kyoto at a Crossroads, A Choice for the Future

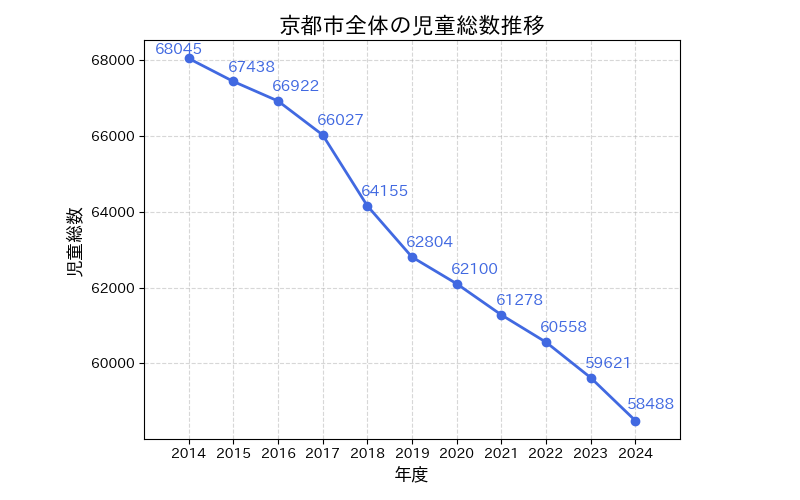

1. A Shocking Reality: A Decline of 10,000 Students in 10 Years, Equivalent to One Elementary School Vanishing Annually

First, let’s examine the change in the total number of elementary school students across Kyoto City over the last decade as a starting point for our discussion. The reality shown in this first graph is more severe than expected.

【Graph 1: Transition in the Total Number of Students in Kyoto City】

The number of students in the city, which was 68,045 in fiscal year 2014, has plummeted to 58,488 in fiscal year 2024. The number of children lost over this 10-year period is a staggering 9,557. This represents a decrease of approximately 14%, meaning that on average, over 950 children are lost each year—a decline equivalent to an entire medium-sized elementary school disappearing annually.

| Fiscal Year | Number of Elementary School Students |

| 2014 | 68,045 |

| 2015 | 67,438 |

| 2016 | 66,922 |

| 2017 | 66,027 |

| 2018 | 64,155 |

| 2019 | 62,804 |

| 2020 | 62,100 |

| 2021 | 61,278 |

| 2022 | 60,558 |

| 2023 | 59,621 |

| 2024 | 58,488 |

Even considering Japan’s nationwide declining birthrate, this pace of decrease is an abnormal situation. The biggest factor behind this, as pointed out in a Toyo Keizai Online article, is the out-migration of young people and families with children from the city. The surge in land prices and rents directly impacts their residential choices. Raising children requires a certain amount of living space, and the financial burden of this is extremely heavy in Kyoto City, especially in convenient areas. As a result, they are forced to move to neighboring cities like Otsu and Kusatsu in Shiga Prefecture, or to bedroom communities in Osaka Prefecture that are within commuting distance, in search of a better living environment at a more affordable price.

Kyoto City itself officially acknowledges this issue and has set a goal to become a “city of choice” for young people and families with children, but this data presents the harsh reality that, on the contrary, it is not being chosen.

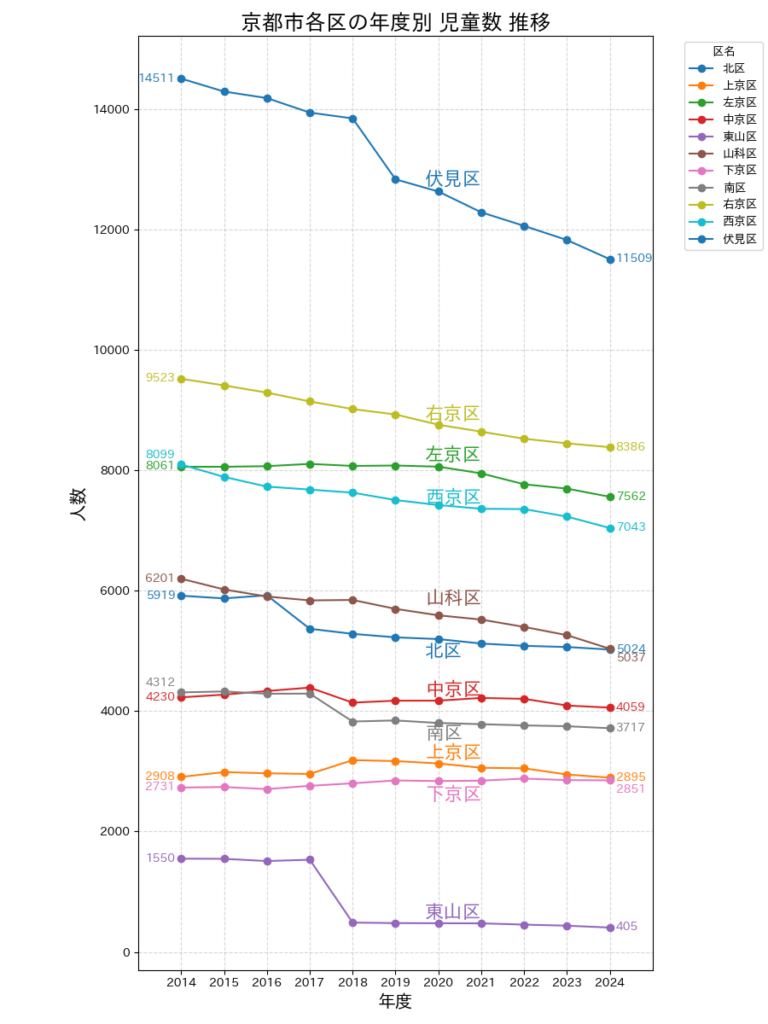

2. The Hollowing Out of the Center, The Vanishing of Communities: Disparity Revealed by Ward-Specific Data

While the city-wide numbers are concerning, the breakdown by the city’s 11 wards reveals the deeper roots of the problem. The decrease in the number of students is not occurring uniformly across the city.

【Graph 2: Transition in the Number of Students by Ward in Kyoto City】

The most shocking data is from Higashiyama Ward, which is also the center of tourism. The number of students, which was 1,550 in fiscal year 2014, has dropped to a mere 405 in fiscal year 2024. The three elementary schools in 2017 became only one in 2018. The 74% decrease over 10 years is at a level where the very existence of the local community is in danger. This trend strongly reflects the aspect of “tourism pollution,” where old residential areas have been bought up and transformed into hotels, high-end inns, and commercial facilities due to the explosive increase in inbound tourism demand, literally “driving out” residents.

A similar trend is seen in other central urban areas. In these regions, a close-knit lifestyle where people lived and worked together once existed, and the voices of children attending local schools were a part of the daily scenery. Now, the children who are the future of these communities are rapidly disappearing, and the function of the city itself is changing from a “place to live” to a “place to visit.” Meanwhile, suburban wards like Fushimi and Ukyo are also experiencing a decline, but the pace is not as rapid as in the central areas. This regional difference indicates that Kyoto City’s problem is not just population decline, but a distortion of its urban structure.

Even though there was a consolidation of elementary schools in Shimogyo Ward, the overall number of students has increased due to its convenience and more affordable land prices resulting from land development. However, land prices around Kyoto Station are still rising sharply, and it remains uncertain how much area will be secured for residential use.

3. The Light and Shadow of the Educational Field: The Benefits of Small Classes and the Crisis of School Survival

The decrease in the number of students naturally has a direct impact on schools, the very heart of daily education. There, a seemingly positive aspect coexists with a serious challenge.

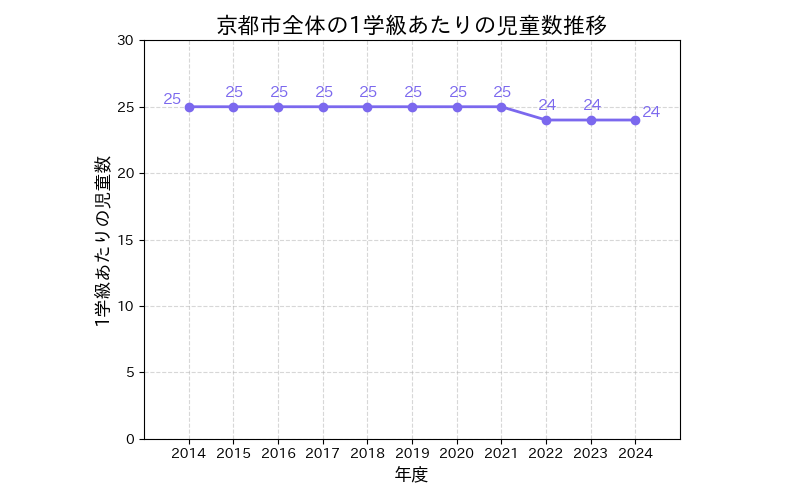

【Graph 2: Transition in the Number of Students Per Class】

First, the “light” side is the change in the number of students per class. This number, which had been around 25 for many years, decreased to 24 in fiscal year 2022 but has remained largely unchanged. The quality of “small classes,” which allows teachers to spend more time with each student and provide more detailed guidance, is being maintained.

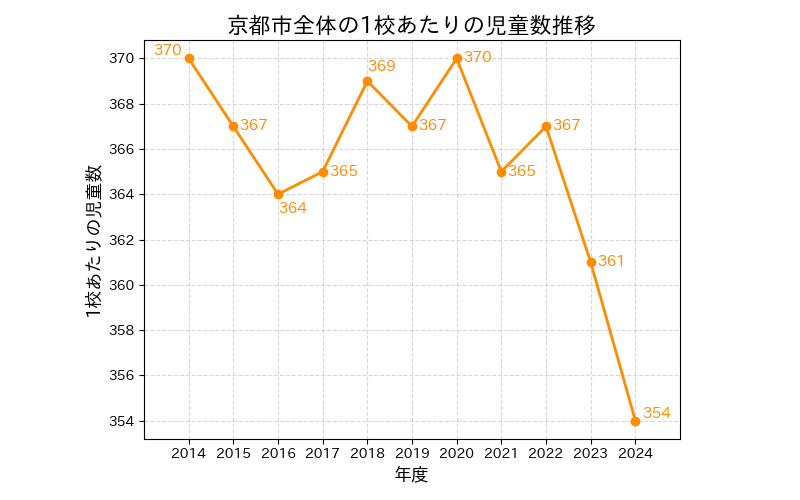

【Graph 3: Transition in the Number of Students Per School】

However, a serious “shadow” lurks beneath the surface. Graph 3 shows that the “number of students per school” has consistently decreased, from 370 in fiscal year 2014 to 354 in fiscal year 2024. In addition, the number of elementary schools has decreased from 184 in 2014 to 165 in 2024.

This indicates that schools themselves are becoming smaller, which poses numerous challenges. For example, it could reduce opportunities for children to build diverse friendships, potentially hindering the development of social skills. It could also make it difficult to maintain after-school clubs (especially team sports) that require a certain number of participants, and school events might be scaled down, narrowing the range of activities children can experience.

In the future, if schools become even smaller, consolidation will be inevitable. Consolidation not only increases the commuting burden on children but also risks stripping schools of their long-standing role as the core of the community, which could trigger further regional decline.

4. A New Trend: Hope and Challenges Brought by Diversifying Nationalities

While the total number of students in the city is on a declining trend, there is one interesting data point that shows a completely different movement: the number of foreign students.

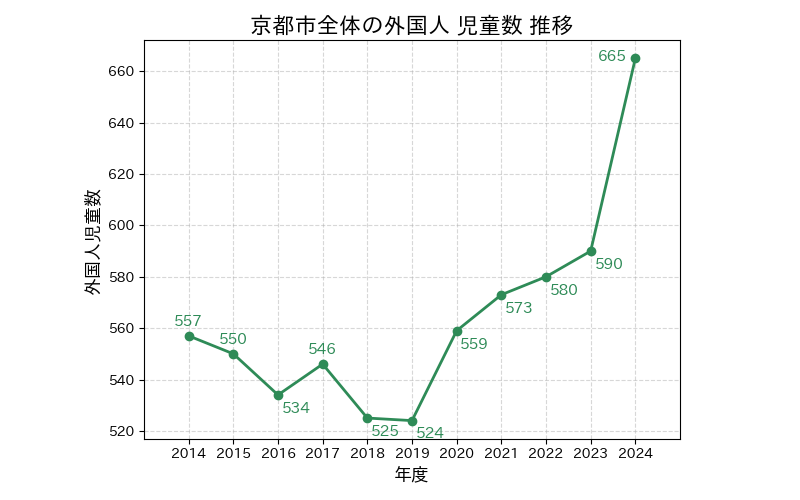

【Graph 4: Transition in the Number of Foreign Students in Kyoto City】

The number of foreign students has been on an upward trend since a low of 524 in fiscal year 2018, with the pace of increase becoming particularly noticeable since fiscal year 2022 when COVID-19 border restrictions were eased. It reached 665 in fiscal year 2024, the highest number in the last 10 years. This reflects Kyoto’s status as a hub for universities and research institutions, as well as a global tourist city that attracts international talent.

The fact that the number of foreign students is increasing while the number of Japanese students is decreasing means that the composition of students in the city’s elementary schools is becoming more diverse and international. This holds the potential to create immeasurable educational value, allowing children to be exposed to different cultures and values from an early age and naturally acquire a global mindset.

However, at the same time, this places new demands on the education system. The need for enhanced support systems for children who require Japanese language instruction (JSL education), multilingual support for smooth communication with parents, and the establishment of an inclusive educational environment where all students can respect each other’s cultural backgrounds is becoming more urgent than ever. The ability of the administration and the education sector to transform this new wave of change into a strength for Kyoto’s education is now being tested.

Conclusion: Kyoto at a Crossroads, A Choice for the Future

A multi-faceted analysis of 10 years of data reveals a harsh reality: Kyoto City has significantly lost the balance between its development as a “cultural and tourist city” and its function as a “livable city where citizens raise their children.” The soaring land prices brought about by the booming tourism industry have led to the outflow of families with children—the very generation that holds the future—from the city, as a result, drastically reducing the number of children who are the source of vitality for the community.

Of course, Kyoto City is not sitting idly by. The “Kyoto City Basic Plan” advocates for strengthening housing and employment policies to make the city a preferred choice for young people and families with children. However, to reverse the irreversible 10-year trend shown by the data, more fundamental and bold policies that are closer to the lives of citizens are needed.

Culture and tourism are only deepened in charm when people live there and a way of life is maintained. A city from which residents have left and the voices of children can no longer be heard has no sustainable future. Is the city able to genuinely listen to the silent cry of citizens expressed in the data—the “exodus from Kyoto”—and seriously tackle the redevelopment of housing policies, urban planning, and the educational environment? Kyoto now stands at a major crossroads that will determine its future.

Sources